What is Event Sourcing, and when to use it?

In Event sourcing all data from all events that modify data are retained.

Event Sourcing is a software application architecture that focuses on storing the details of every event that occurs in the business domain. After every event is stored, views are generated from events which makes it easy to utilize your data. Because views are a derivative of the event store, the event store is a 100% reliable audit log of all changes to the domain. This architecture was popularized by Greg Young and is used by financial trading systems, banking systems, gambling, large e-commerce applications, and more. This article explains why event sourcing can be beneficial, how it works, and some potential drawbacks.

Which applications benefit from Event Sourcing?

- Applications that must not lose data.

- Applications needing a reliable audit log.

- Applications requiring a high level of governance regarding changes to data.

- Applications where a high level of scalability is desired or required.

Event Sourced systems never lose data

What does it mean to ‘lose data’?

If there is more than one way your data could have come into its current state, and you can’t tell how came to that state, then you have lost data. You would not be able to provide a reliable audit trail. You have lost valuable data for analytics. You have lost the steps required to get the data from a starting point to its current state. In addition, you can’t prove that your data is correct.

Most applications that use a relational database to store data are losing data because relational databases typically only store the current state of the system.

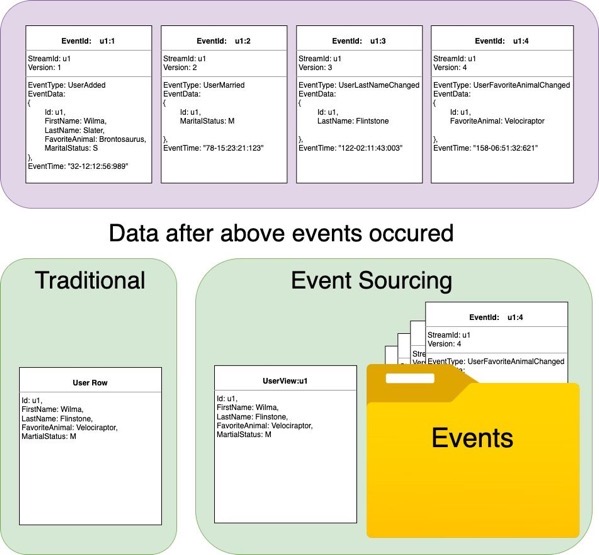

Traditional vs Event Sourced Systems

Here are a set of events that occurred in chronological order in a system. Then we see how a traditional relational database holds the data versus how an event-sourced system stores the data.

Both systems keep a current state view of the data, and the Event Sourced system also saves every event that occurred over time.

Imagine that a data scientist working for the company discovers from her analysis that (1) married people, who (2) like velociraptors, and (3) previously liked brontosauruses when (4) they were still single, are very likely to want to purchase a new species of family pet called a “Bronto-raptor”. If the company uses Event Sourcing, they can easily find the people in their system that they should market to. If they have a traditional system, then they have thrown away the data needed to find the target customers.

Based on that example it should be easy to imagine the benefits of analyzing data from an event-sourced system and how that could reveal important insights regarding finance, security, and healthcare.

How does Event Sourcing work?

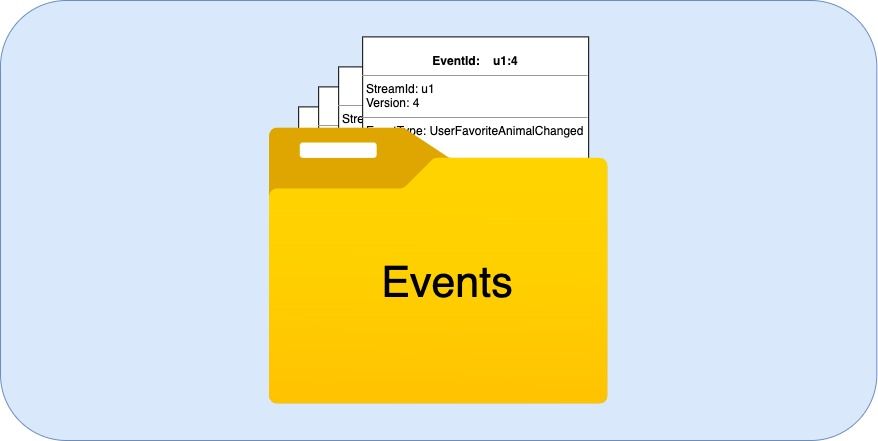

The primary artifact of an Event Sourced system is a collection of events. Every event which can change the state of the data is recorded. We are less concerned with the current state of the data than we are with capturing the details of every individual event and preserving those. By having all those events, we can construct the current state of data as needed.

Because we record every event and then build our current state from the recorded events, we have a 100% accurate audit log. We have the ability to replay the events. Every time we replay our events, using a given set of logic, we can be guaranteed the exact same outcome. If there is ever a dispute about our current state, we can replay our events one by one, from the beginning to end, to show how we arrived at our current state.

A familiar example of an event-sourced system that has been in use for hundreds of years, is an accounting register. In event-sourcing terms, the accounting register is a ‘stream’. The ‘stream’ is filled with a series of events in the order that they occur. We know through mathematical proofs and hundreds of years of experience, that recording events in this manner provides an accurate and auditable record of events without losing data. If we apply the same logic to the set of events we know we will get the exact same results every single time.

An interesting benefit of event-sourcing is that you can take a given set of events and apply variations of logic to them, to run ‘what if’ scenarios.

Rules of Event Sourcing

Rule 1: Events are immutable. We never erase, delete, or alter events.

In event-sourcing, we never mutate an existing event. We never erase, delete, or alter a recorded event. All we can ever do is add more events to our system. Every new event is a new fact that we add to our history of facts. New facts are appended to the end of the log of events.

Event-sourcing follows the same rules that accountants follow when recording transactions in a journal. Accountants record every individual event as a journal entry. If the accountant makes a mistake or puts incorrect data into the journal, they NEVER erase, delete, or alter the incorrect entry after it is added to the system. To correct a mistake, they will make compensating journal entries to offset the incorrect entry and this brings the current balance into the desired state. We follow the same practice in Event Sourcing.

Rule 2: Events must be stored in chronological order

In mathematics, there is a commutative rule for addition and multiplication that states that you can commute (or move around) the numbers in an equation and still arrive at the same answer. This is not true for all types of equations and is certainly NOT true for event-sourcing. Maintaining the order of events in an event stream is critical.

Why we must follow the rules:

I grew up in the 1980’s and Back the Future movies were popular then. When the professor and Marty traveled to the past, the professor warned Marty to be careful about changing any events, no matter how insignificant, because that could have drastic unforeseen consequences on the future. This is easy to see in an event-sourced system. This is true in event sourcing too. In fact, if you alter an event, you are changing history. Think of your event store as your history.

Imagine the following events occurring in this order:

- BuyCar(Id=123, Owner=“Molly”, Model=2022, Brand=“Ford”, Color=“White”);

- PaintCar(Id=123, Color=“Blue”)

- PaintCar(Id=123, Color=“Red”)

After these events occur, Molly is the owner of a red 2022 Ford.

It is easy to see that if we change the order of the events (even a little bit), we will have a drastically different outcome.

- BuyCar(Id=123, Owner=“Molly”, Model=2022, Brand=“Ford”, Color=“White”);

- PaintCar(Id=123, Color=“Red”) // changed order of this event

- PaintCar(Id=123, Color=“Blue”)

If we play the events in this order, then Molly would have a blue car. Event order matters in event sourcing so we must make sure that we are able to process our events in chronological order.

How do we get the current state from a stream of events?

The naive approach to getting the current state of a stream would be to replay all the events from the beginning of time to the current time. Taking the accounting journal example, if we needed to get the current balance for an account, we could start at zero, add all the journal entries (events), in the same order that they originally occurred, and we could arrive at our current balance. After all that work, we would certainly have the correct answer.

If we only needed to see that current balance one time, this might be a reasonable approach, but if we need to get that value multiple times, it would be a lot of work to do that every time we want the current balance. Especially as our journal grows to contain thousands or millions of entries.

Views for current state:

A better approach would be to create a cached view that contains a currentBalance property along with the identifier of the last event the cached view accounted for. Every time a new event is recorded in our journal, that event could trigger an update to our cached view, which would update the currentBalance field and note the event that caused the update. The next time we need the balance we can just look at our cached view and know it would be up to date for the last event that it accounted for. Because this allows for a fast and efficient way to read current state data from our system, this is how most event-sourced systems work.

How to build an Event Sourced Application

Based on what we have learned, writing our data should be very simple. We record new events by appending them to the end of the list of all previously recorded events.

We also learned that we can use views to store a cache of current state data, which can be read quickly on demand. Because of this, it makes sense to have 2 data stores. One data store will contain all the events. The other will contain views that match the expected requests for data.

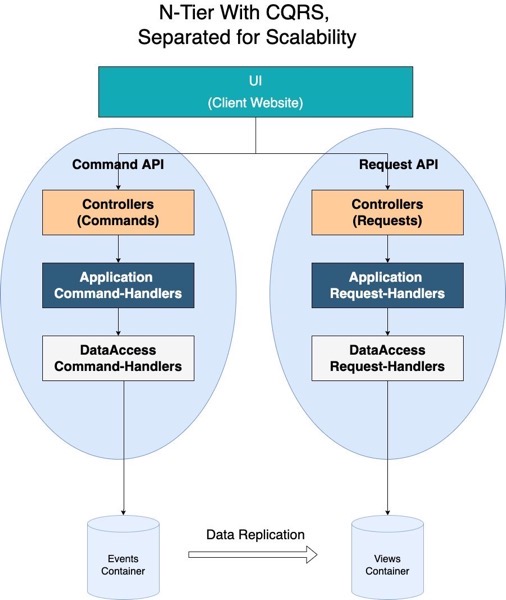

CQRS:

This would be a good time to introduce a design pattern that is meant for separating the task of writing data from the task of querying data. The pattern is called CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation). In the simplest terms, it separates the code that changes data (Commands) from the code that reads data (Requests). CQRS can be used without event sourcing, but it is very well suited for event sourcing. We have already decided that it makes sense for us to have 2 data stores: an Events container and a Views container. Because of this, it is very easy for us to keep our code that writes events in one place, which is connected to the Events container, and to keep our code that reads views in another place connected to our Views container.

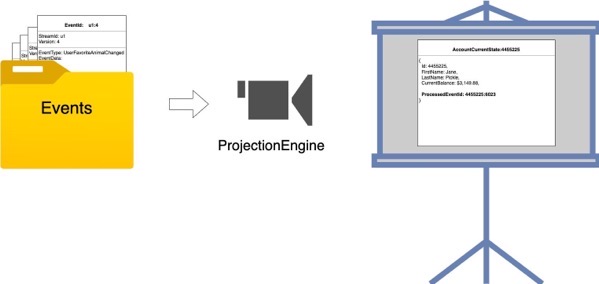

Keeping the Views container updated:

We have not discussed yet how the Views container gets updated. We need to build a Projection Engine. ‘Projection’ is another word for ‘view’ so the Projection Engine builds projections or ‘views’’. The Projection Engine will watch every event that is added to the Events container and update views that need to be updated. This can happen right after the event is stored in the Events container. The time it takes for the Projection Engine to acknowledge the event occurred, and update a view is the lag time for the eventual consistency between the Event container and the Views container.

The Eventual Consistency Problem:

In our accounting example above we created a cached view of our account balance so that when we need the balance, we don’t need to step through every event in the journal and process them every time. This made it efficient for us to quickly read the current balance from a view. Above we decided to record events in one container and views in another container.

What would happen if you requested the view for the account balance at the instant just after an event was recorded in the ‘Events Container’?

There are 2 possible answers here:

In a transactional system, the cached view can be updated at the exact same time we update the event and therefore we have 100% consistency between the two data stores. Anytime you request the balance it will be guaranteed to reflect all of the events that have been recorded.

Alternatively, we could have an eventually consistent system in which there is no transaction. The event would be recorded. Then a moment later, the Projection Engine would be triggered to update our view.

I am sure that there are “transactional” event-sourced systems being built, however, it is not the preferred approach. In event sourcing, it is more common to have eventually consistent systems. This is a key point to gaining scalability.

CAP Theorem:

Because we are creating a system that has more than one data store, we have a distributed data store. Distributed data stores are beneficial because they allow us to replicate data in more than one place and they allow us to scale. Distributed data stores are subject to the CAP Theorem which states that only 2 out of 3 of the following guarantees can be provided:

- Consistency

- Availability

- Partition Tolerance

In Event Sourced systems, we typically give up Consistency in order to guarantee Availability and Partition Tolerance.

When explaining this caveat to the business, you might meet resistance. It is common for people to believe that 100% consistency is necessary. We tend to think we need everything to consistent, however many systems we deal with are not fully consistent and we are just fine with that. For instance, if you deposit $100 to your bank account and it takes 1 second for that $100 to appear in your updated balance, would that really be a problem? I’m in the US, where it can takes days for my bank account to become consistent with the transactions I’ve executed. So what if it takes 5 seconds or 60 seconds? It really comes down to expectations. As long as the update to the Views occurs within a time that meets expectations everyone is fine with eventual consistency. There are times eventual consistency is ok, and there are times when it is not acceptable. It will be up to you to decide if it is acceptable for your application.

Scalability:

Efficient for recording data:

One nice thing about event sourcing is that we can build our code to be very fast and efficient for writing data. We don’t need to concern ourselves with efficiency for updating or deleting events because that never happens.

We just need to write our code so it can drop events into our database. Since we always append events to the end of the existing stream, we don’t have to worry about re-indexing and shuffling data around. Because of this, we can build code that is extremely fast at recording events.

Efficient for reading data:

Because we are using Projections (views) that have been prepared when events occurred, we don’t need complex queries as we would in a relational database, when data is requested. Instead, we can design views that are ready to provide exactly what we need, and they are available when we need them. The data is ready and waiting so it is equivalent to a ‘select by index’ query. This is very fast and efficient.

Because we use CQRS, it is possible to put all our Command logic in one code-base, and all our Request logic in another code-base, which means we can scale our read side separately from the write side. This is helpful because systems typically are much heavier on one side than the other. We can scale our resources exactly where we need to without wasting resources to overpower the other side.

Summary:

In this introduction, we have identified what Event Sourcing is, and have shown that it is a well-proven system that has been used for hundreds of years. EventSourced systems are usually designed to be eventually consistent to take advantage of the scalability that allows. We introduced CQRS as a design pattern that is well suited for building Event Sourced systems. Event Sourced systems provide a complete audit trail of all events which is critical for financial systems or any system where security and audibility are required. I hope this will encourage you to learn more about Event Sourcing and how to apply it to your applications.

Glossary:

Aggregate: An object with an identifier (Id).

Projection: A cached view of data. In event sourcing, a project represents a view of data at a certain point in time.

Stream: A collection of events documenting changes to an aggregate. The events in a stream share a single Id that matches the aggregate Id, and they track their place in chronological order. The stream represents all the events that affect a single aggregate.

Leave a comment